The Novel I Didn’t Mean to Write

How a novel that began as satire became something else entirely: a story about awareness, silence, and what it means to tell the truth when comfort is easier.

I didn’t set out to write about systemic bias or white privilege. I set out to write a clever satire: Groundhog Day meets Office Space. A man working at a direct selling company, trapped in random time loops, mentored by a Franz Kafka visiting from a parallel universe. Then 2020 happened: George Floyd, the protests, the pandemic lockdowns.

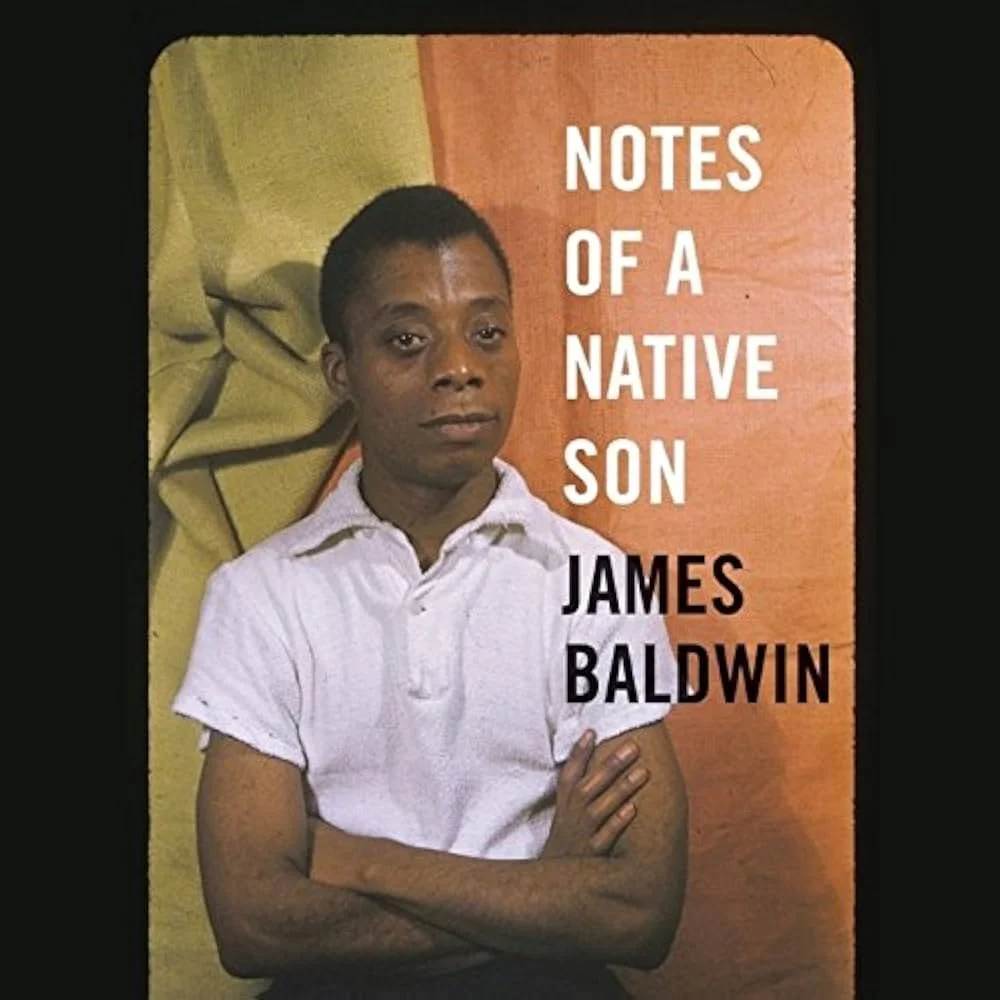

Writers like Baldwin had already wrestled with the country’s fractures, and I began seeking them out. Their voices pulled me in, not for research but for comprehension.

The books changed my perspective and exposed blind spots. I hadn’t planned for my novel to engage with those ideas, but I started to feel that it couldn’t ignore them.

The more I read, the more those themes demanded a place in the story. Soon, the protagonist had to face his own apathy, layered in cultural depth, and even echoed John Brown’s trial speech at the novel’s climax. But the story felt stitched together, the themes tacked on. The depth I tried to add felt flat.

The turning point came when I read James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son.

Baldwin didn’t simplify pain, race, or identity—he complicated them, showing that truth in writing doesn’t come from moral clarity or big themes alone, but from confronting contradictions.

He argued that novels should show the world honestly, in all its complexity. Baldwin criticized Native Son and Uncle Tom’s Cabin as “protest novels” that traded humanity for moral messaging.

A light bulb went on. I had written one too, and I had a mess on my hands.

I spent five years as a product manager in a direct selling company. Product managers have a unique vantage point. They talk to everyone—from executives to customers—and see how decisions are made, avoided, and where accountability quietly disappears.

Direct selling is the epitome of contradiction, particularly with the MLM model. It promises entrepreneurship and community while concentrating rewards at the top. It preaches family values while treating people like numbers on a spreadsheet—laying off employees while maintaining the landscaping budget. It invents inspiring origin stories, only to abandon them when research reveals a more profitable narrative.

Executives preach hard work and a growth mindset in a world where management remains predominantly white, male, or related by blood. Although not formally required, religious affiliation seems to function as an unspoken credential for leadership roles.

The people I worked with were mostly kind, sincere, and living the life they believed in. They were authentic. Of course, not everyone at a company buys into the culture—sometimes it’s just a paycheck and health insurance. And without knowing someone, assumptions and conclusions aren’t fair.

What struck me most as an employee was the everyday contradiction: how we take part in something flawed and justify it, whether out of convenience or because the alternative feels like betrayal.

But my earlier drafts didn’t really address this, not directly. And when it did, the characters were flat and caricatures, just as Baldwin warned. I had avoided the difficult truths. I was afraid to expose the darker corners of the story, to let it go where it needed to. That was the novel I had written, not deliberately but unavoidably.

I realized that the book didn’t need editing. It required a teardown.

So I cut the Kafka character. Scrapped the time loop. Rebuilt Cody’s arc from scratch. I stopped trying to write a message and started trying to write a mirror.

The story was no longer about redemption. It was about recognition and courage. It asked whether awareness is ever enough, what silence costs, and how comfort sustains the status quo.

And yet, for a story about awareness and silence, one absence speaks loudest.

Even though the novel deals with systemic bias and corporate entitlement, there is only one main nonwhite character. That absence isn’t accidental or careless. It reflects the world of direct selling—a space that speaks endlessly about opportunity and inclusion while remaining overwhelmingly white. To invent diversity where it didn’t exist would have been dishonest. The lack of representation isn’t the problem I created; it’s the problem the story reveals.

Of course, I knew this wouldn’t fly in traditional publishing. A debut white male author, writing about institutional racism and bias with a white male protagonist? A predominantly white cast? It looks like the same story we’ve seen a hundred times.

It looks familiar, but the choice is deliberate.

The story had to be told from inside the bubble, because that’s where privilege lives.

Cody knows the world is unfair, but keeps trying to fix just his corner of it. He sees the issues, even feels them, but can’t yet admit he benefits from the same system he quietly despises. His story lives in that tension between awareness and avoidance.

He’s the lens, not the lesson. Through his perspective, the novel exposes the quiet hypocrisies of privilege, corporate culture, and self-delusion—not to redeem him, but to hold him accountable. Cody’s journey isn’t about becoming a savior; it’s about seeing what he’s been part of all along.

I’ve always been drawn to a simple but unsettling question: why do some people challenge the status quo, while others defend it—even when it harms them?

This novel doesn’t answer that question. It isn’t meant to.

But it asks the question honestly, through a character forced to reckon with what he’s part of, and what it might cost him to take a stand.

I didn’t write this book to be forgiven. I wrote it to understand what it takes for someone like Cody, and someone like me, to stop looking away.

Whether you see yourself in him or recognize someone you know, I hope this story gives you a little space to sit with the question of why we defend the systems that harm us and to carry that question a little longer than before.